Before answering this it’s important to know the big questions, and not just from the scientific point of view. But it’s a good starting point.

New Scientist latest edition 2018 starts with:

The biggest questions ever asked

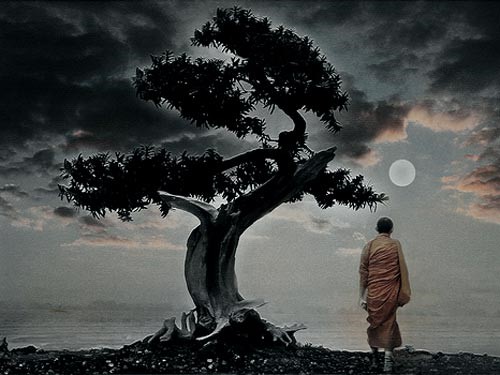

(Image: H. Koppdelaney / Hartwig HKD)

THE BIGGEST QUESTIONS EVER ASKED

We celebrated New Scientist magazine’s 50th birthday by asking some of science’s leading lights to explore the biggest questions of our time. You can find out what they had to say by following the links below.

1. The Big Questions: What is reality?

Can we be sure that the world we experience is not just a figment of our imaginations, asks Roger Penrose

2. The Big Questions: What is life?

If we encountered alien life, chances are we wouldn’t recognise it – not even if it were here on Earth, says Robert Hazen

3. The Big Questions: Do we have free will?

The more we find out about how the brain works, the less room there seems to be for personal choice or responsibility, says Patricia Churchland

4. The Big Questions: Is the universe deterministic?

However you look at it, the answer seems to be “maybe”, says Vlatko Vedral

5. The Big Questions: What is consciousness?

How does the brain, with its diverse distributed functions, come to arrive at a unified sense of identity, asks Paul Broks

6. The Big Questions: Will we ever have a theory of everything?

2000 years of rational enquiry may be approaching their crowning glory. Just one more push could be enough, says Michio Kaku

7. The Big Questions: What happens after you die?

We have all wondered if there is an afterlife, but only a few are brave – or foolish – enough to try and find out, says Mary Roach

8. The Big Questions: What comes after Homo sapiens?

All species are fated either to die out or to evolve into something else – all except humans, who have a chance of a transcendent future, says James Hughes

Before I start answering let’s look at a few more, these were found on gizmodo.

PHYSICS

8 Great Philosophical Questions That We’ll Never Solve

Philosophy goes where hard science can’t, or won’t. Philosophers have a license to speculate about everything from metaphysics to morality, and this means they can shed light on some of the basic questions of existence. The bad news? These are questions that may always lay just beyond the limits of our comprehension.

Here are eight mysteries of philosophy that we’ll probably never resolve.

1. Why is there something rather than nothing?

Our presence in the universe is something too bizarre for words. The mundaneness of our daily lives cause us to take our existence for granted — but every once in a while we’re cajoled out of that complacency and enter into a profound state of existential awareness, and we ask: Why is there all this stuff in the universe, and why is it governed by such exquisitely precise laws? And why should anything exist at all? We inhabit a universe with such things as spiral galaxies, the aurora borealis, and SpongeBob Squarepants. And as Sean Carroll notes, “Nothing about modern physics explains why we have these laws rather than some totally different laws, although physicists sometimes talk that way — a mistake they might be able to avoid if they took philosophers more seriously.” And as for the philosophers, the best that they can come up with is the anthropic principle — the notion that our particular universe appears the way it does by virtue of our presence as observers within it — a suggestion that has an uncomfortably tautological ring to it.

2. Is our universe real?

This the classic Cartesian question. It essentially asks, how do we know that what we see around us is the real deal, and not some grand illusion perpetuated by an unseen force (who René Descartes referred to as the hypothesized ‘evil demon’)? More recently, the question has been reframed as the “brain in a vat” problem, or the Simulation Argument. And it could very well be that we’re the products of an elaborate simulation. A deeper question to ask, therefore, is whether the civilization running the simulation is also in a simulation — a kind of supercomputer regression (or simulationception). Moreover, we may not be who we think we are. Assuming that the people running the simulation are also taking part in it, our true identities may be temporarily suppressed, to heighten the realness of the experience. This philosophical conundrum also forces us to re-evaluate what we mean by “real.” Modal realists argue that if the universe around us seems rational (as opposed to it being dreamy, incoherent, or lawless), then we have no choice but to declare it as being real and genuine. Or maybe, as Cipher said after eating a piece of “simulated” steak in The Matrix, “Ignorance is bliss.”

3. Do we have free will?

Also called the dilemma of determinism, we do not know if our actions are controlled by a causal chain of preceding events (or by some other external influence), or if we’re truly free agents making decisions of our own volition. Philosophers (and now some scientists) have been debating this for millennia, and with no apparent end in sight. If our decision making is influenced by an endless chain of causality, then determinism is true and we don’t have free will. But if the opposite is true, what’s called indeterminism, then our actions must be random — what some argue is still not free will. Conversely, libertarians (no, not political libertarians, those are other people), make the case for compatibilism — the idea that free will is logically compatible with deterministic views of the universe. Compounding the problem are advances in neuroscience showing that our brains make decisions before we’re even conscious of them. But if we don’t have free will, then why did we evolve consciousness instead of zombie-minds? Quantum mechanics makes this problem even more complicated by suggesting that we live in a universe of probability, and that determinism of any sort is impossible. And as Linas Vepstas has said, “Consciousness seems to be intimately and inescapably tied to the perception of the passage of time, and indeed, the idea that the past is fixed and perfectly deterministic, and that the future is unknowable. This fits well, because if the future were predetermined, then there’d be no free will, and no point in the participation of the passage of time.”

4. Does God exist?

Simply put, we cannot know if God exists or not. Both the atheists and believers are wrong in their proclamations, and the agnostics are right. True agnostics are simply being Cartesian about it, recognizing the epistemological issues involved and the limitations of human inquiry. We do not know enough about the inner workings of the universe to make any sort of grand claim about the nature of reality and whether or not a Prime Mover exists somewhere in the background. Many people defer to naturalism — the suggestion that the universe runs according to autonomous processes — but that doesn’t preclude the existence of a grand designer who set the whole thing in motion (what’s called deism). And as mentioned earlier, we may live in a simulation where the hacker gods control all the variables. Or perhaps the gnostics are right and powerful beings exist in some deeper reality that we’re unaware of. These aren’t necessarily the omniscient, omnipotent gods of the Abrahamic traditions — but they’re (hypothetically) powerful beings nonetheless. Again, these aren’t scientific questions per se — they’re more Platonic thought experiments that force us to confront the limits of human experience and inquiry.

5. Is there life after death?

Before everyone gets excited, this is not a suggestion that we’ll all end up strumming harps on some fluffy white cloud, or find ourselves shovelling coal in the depths of Hell for eternity. Because we cannot ask the dead if there’s anything on the other side, we’re left guessing as to what happens next. Materialists assume that there’s no life after death, but it’s just that — an assumption that cannot necessarily be proven. Looking closer at the machinations of the universe (or multiverse), whether it be through a classical Newtonian/Einsteinian lens, or through the spooky filter of quantum mechanics, there’s no reason to believe that we only have one shot at this thing called life. It’s a question of metaphysics and the possibility that the cosmos (what Carl Sagan described as “all that is or ever was or ever will be”) cycles and percolates in such a way that lives are infinitely recycled. Hans Moravec put it best when, speaking in relation to the quantum Many Worlds Interpretation, said that non-observance of the universe is impossible; we must always find ourselves alive and observing the universe in some form or another. This is highly speculative stuff, but like the God problem, is one that science cannot yet tackle, leaving it to the philosophers.

6. Can you really experience anything objectively?

There’s a difference between understanding the world objectively (or at least trying to, anyway) and experiencing it through an exclusively objective framework. This is essentially the problem of qualia — the notion that our surroundings can only be observed through the filter of our senses and the cogitations of our minds. Everything you know, everything you’ve touched, seen, and smelled, has been filtered through any number of physiological and cognitive processes. Subsequently, your subjective experience of the world is unique. In the classic example, the subjective appreciation of the colour red may vary from person to person. The only way you could possibly know is if you were to somehow observe the universe from the “conscious lens” of another person in a sort of Being John Malkovich kind of way — not anything we’re likely going to be able to accomplish at any stage of our scientific or technological development. Another way of saying all this is that the universe can only be observed through a brain (or potentially a machine mind), and by virtue of that, can only be interpreted subjectively. But given that the universe appears to be coherent and (somewhat) knowable, should we continue to assume that its true objective quality can never be observed or known? It’s worth noting that much of Buddhist philosophy is predicated on this fundamental limitation (what they call emptiness), and a complete antithesis to Plato’s idealism.

7. What is the best moral system?

Essentially, we’ll never truly be able to distinguish between “right” and “wrong” actions. At any given time in history, however, philosophers, theologians, and politicians will claim to have discovered the best way to evaluate human actions and establish the most righteous code of conduct. But it’s never that easy. Life is far too messy and complicated for there to be anything like a universal morality or an absolutist ethics. The Golden Rule is great (the idea that you should treat others as you would like them to treat you), but it disregards moral autonomy and leaves no room for the imposition of justice (such as jailing criminals), and can even be used to justify oppression (Immanuel Kant was among its most staunchest critics). Moreover, it’s a highly simplified rule of thumb that doesn’t provision for more complex scenarios. For example, should the few be spared to save the many? Who has more moral worth: a human baby or a full-grown great ape? And as neuroscientists have shown, morality is not only a culturally-ingrained thing, it’s also a part of our psychologies (the Trolly Problem is the best demonstration of this). At best, we can only say that morality is normative, while acknowledging that our sense of right and wrong will change over time.

8. What are numbers?

We use numbers every day, but taking a step back, what are they, really — and why do they do such a damn good job of helping us explain the universe (such as Newtonian laws)? Mathematical structures can consist of numbers, sets, groups, and points — but are they real objects, or do they simply describe relationships that necessarily exist in all structures? Plato argued that numbers were real (it doesn’t matter that you can’t “see” them), but formalists insisted that they were merely formal systems (well-defined constructions of abstract thought based on math). This is essentially an ontological problem, where we’re left baffled about the true nature of the universe and which aspects of it are human constructs and which are truly tangible.

So far the two articles.

Have you noticed something here?

Philosophy goes where hard science can’t, or won’t, at least that’s what this article tells us, it also tells us: 8 Great Philosophical Questions That We’ll Never Solve, but number 7 in the list of the New Scientist is: The Big Questions: What happens after you die? True, they do not mention god, but the life after death question is certainly not one to be expected. And in order to answer these questions we need to look at this, and the best way to do that is to look at another question they have, Why Physicists Need Philosophers? This is what they say: There’s a spat brewing between some theoretical physicists and philosophers of science recently, and NPR’s Adam Frank has all the details. It started when one philosopher of science, David Albert, questioned the notion that the universe came “from nothing,” as the title of Laurence Krauss’ new book claims. This quickly escalated into a debate over whether philosophy of science was even a worthwhile endeavour, or just a distraction from the hard, nuts-and-bolts work of figuring out the nature of the universe. Frank has a great explanation of just why these physicists are wrong to dismiss philosophy out of hand:

Richard Feynman was famously scornful of the philosophy of science. He thought it was immune to finding relevant results or making real progress. But the problem is that we aren’t living in Richard Feynman’s age of physics anymore. Something strange happened on the way to the modern intersection of cosmology and foundational physics. Some measure of philosophical sophistication seems helpful, if nothing else, in confronting this new landscape.

It’s one thing for physicists exploring carbon nanotubes to say they have no use for philosophy. Their work lives or dies by experimental data that can be collected tomorrow. But over the last few decades, cosmology and foundational physics have become dominated by ideas that appear to take a page from science fiction and, more importantly, remain firmly untethered to data.

Concepts like hidden dimensions of reality (string theory) or hidden infinite possible parallel universes (the multiverse) are radical revisions of the very concept of reality. Since detailed contact with experimental data might be decades away, theorists have relied mainly on mathematical consistency and “aesthetics” to guide their explorations. In light of these developments, it seems absurd to dismiss philosophy as having nothing to do with their endeavours.

I would like to suggest to read Adam Frank’s blog NPR to get an idea about the ongoing debate between science and religion. Plus working our way to the single one question that when answered can solve all of them.

If we look at these 16 questions, could we bring them down a few? Some of you might expect me to work my way to the question of numbers, or yet others might expect me to point to God. Or life after death, but consider this, would there be one that would answer several? True if I could directly show the existence of God then many would fall away and if I were to answer some then it would still leave open others.

Yet I still like to start with God and see if we find an answer by looking what (he) has to say about himself. If we look at most of the names given in the Bible, then we can conclude that most are describing qualities, redeemer, creator, merciful, compassioned etc., we could say attributes of an unfailing love. The all seeing, all hearing I Am Who I Am. But how can that be a name? Now if any of you haven’t taken the time to study the Bible a little, I suggest you do, even if you didn’t because you might not believe in a God or any religion. To judge without ever having looked and get your opinion from judging those who do and make mistakes in interpretation, or simply because you judge it by the poor judgements of its followers or hear say from other disbelievers is being as blind as those who make those poor judgements.

Because when you did look into it a bit more than having opened the Bible or some of the other religious books, you would have come to see that all these names of the patriarchs are also either qualities or principles. Names had meanings, and most likely your own name at least your surname was derived from either your great great great great grandfather’s job or where he was from or known for. Like the name Abraham means the father of many.

Bear with me a little longer as I will move on to another of the 16 questions shortly, so having established that names are related to a job, quality of some sort or location etc. then His name I AM who I AM must stand for something too, just like all his other names. Now if I were to say, I am who I am, then I mean I am like this or that and I do not change, now if we look at all his qualities we would have to accept that he is a conscious being would we not? Pretty logic I presume, one who does not change his ways or qualities. Now it is also said we were made in his image, and here much confusion came into being too, as most of you who do not wish to believe say there is no old man with a big long beard sitting on a throne somewhere in heaven looking at you listening to your prayers etc. False images indeed, our physical instruments, our senses and body are pretty limited, given the fact that they are only functional in the world of matter, and even in the world of matter it is pretty restricted. Yes, we can train ourselves to hear a little better, run a little faster, jump a little higher or learn more, but that’s about it, we do not see beyond the material world. Yes, I hear you, but I’ve experienced this or that, and what about the outer body experiences you hear about? Exactly like you said OUT of body. But what about having seen this or that move while there was NO body around? Well wasn’t that a material object moving? No, the only thing, be it on a lower scale, that comes close (but still far from it) is consciousness. Without it we would not be aware of anything at all. Science is trying to understand how these mechanical parts such as the brain and body bring about consciousness.

We also hear things such as subconscious, and effects or responses to the environment without being aware of its triggers, but when we look at nature then we must agree that there must at least be some kind of consciousness in animals and plants too, and possibly all matter has some kind of consciousness.

Consciousness is not of the mind, not of the brain or body, it pervades and illuminates the mind and body, its neither part nor a product of the mind. It’s apart from the mind and body, unlike what science says, that consciousness is a product of the brain. Consciousness enables it to function, and it’s not limited by the mind and body, it exists apart from the mind and body also. It’s not here or there in the body. Let’s go back to Plato’s cave a moment, you sitting in front watching the wall, what makes you able to be aware of anything at all? Isn’t it the flame in the back of the cave that enables you to be aware of anything? Now the flame is within the body, but it originates from outside of the cave, but this light would consume you, burn you alive. But your body is the cave, your mind is the stage on the background and the light/fire is what enters your mind and body.

This consciousness is known in the functioning of the mind and body, it’s how we can experience consciousness. Without mind and body consciousness still exists but it can’t be known until we lose our identification.

Now let’s look at light. Due to its reflection something can be known of light. If it shines on a face you may recognize it as part reflects the light, but hide the face, the light is still there but the face is not. Light is not a product of the hand, not a part of it. Now let’s say, and you do know this, we are only aware of a part of the spectrum of light, if we would be able to see the whole spectrum of light then we would have X-ray vision too. Indeed light has those qualities too, it would see right through the hand if your eyes had the full range ability. But its spectrum is even wider than that.

What does it mean? If we die, we are lost? Nothing left? Like the light that isn’t reflected so we cannot see it anymore? Perhaps it is time to remind you of the framework upon which matter is woven, that imprint is still there, cluttered with attachments to material (life) but to some extent freed from its material restrained or heavily loaded. Now the question if we can know the light in all its aspects, where there is no time, where all is instantaneous, where mind is not needed in order to know. Yes, a world of no mind is a world of all mind, of all consciousness, of full awareness. But how do we reach that? And how does it relate to all these other questions? Let’s look at the exercises given in the other articles again before we move to how it relates to the other big questions.

Focus. Where do I focus my mind on, and how much? I do not need to remind you that left to its own devises it can make a hell out of heaven and a heaven out of hell.

To focus, to be the observer, and bringing back your focus when it’s been taken away by thoughts and feelings, two things are involved in the ability to keep your focus, challenge and skill. Let’s take learning to drive a car. They usually take you to a big parking lot where you cannot do a lot of damage, you are all aroused and ready to face the challenge. At first it is great to start the engine and drive away without stalling the engine. Your skill and challenge are in line with each other after a while, but if it were the only thing you do it might cause you to become bored with it, so you need to up the challenge like shifting gears which after a while will flow too, so you need to up the challenge a little again, perhaps now you take your first drive along a country road with little traffic. But too much challenge, like going directly to a very busy time for traffic if your skill is below the level of challenge, then it leads to anxiety, strain, uneasiness etc. But if the challenge and flow are a close match, focus, you need to increase your challenge to meet your ability, but if they are too far apart, then you have to break it down to smaller steps, like starting to drive without having to look at the gear shifter and naturally looking in the mirrors so they don’t take away your focus on the road when you drive in traffic and cause you to feel uncomfortable.

But there are other things that will lead you away from your focus, and that is self-interest.

If I am in it for myself, I am doing it for me, this particular person then will always be tense, how much do I gain, how much do I get, how much have I lost? Then you are not relaxed anymore, selfishness leads to a scattered mind. It can lead to a narrow focus on your own interests and you’ll always be open and vulnerable to insecurity, fear etc. while an unselfish mind is a relaxed mind. So the more you do for others, be it a community, or the wellbeing of others, the more relaxed you are about yourself (I like to remind you of the qualities of the 4 monks).

If I close my eyes there is peacefulness, if I open my eyes I ask what can I do for you (god or others). In this time and age it is usually the other way round, when I close my eyes I think I get filled with all sorts of thoughts and disturbances and when I open my eyes it’s not what can I do for you but what can I get from you. The very opposite of spirituality, and it is called worldliness. So it should be clear what causes a better focus. Then there is this, love leads to focus! What I love automatically my mind is drawn to. It’s easily focused without all sorts of tools or techniques.

So let’s go back and see, does god exist? If we become aware of such consciousness as I just described it would be clear would it not?

Is there life after physical death? It would be clear too, what is life? That would be clear and the only one truly worth living. Do we have free will? Yes but the reality is that there are only two options for you to choose from. Could you really experience objectivity? Yes, you could. And would you not come to see the best moral ways? You would. What are numbers, that too would be as clear as day. As such consciousness that is a complete expression of love and has its bases in wisdom would have made it all and have said, it is good.

Truth, the only one that will answer them all, is not one that would leave any of the other open for questioning. It lies in waking up in that all pervading, all penetrating consciousness of which love is its ultimate expression.

Seek it with all your might, be the 4 monks all in one.

27-07-2018

Moshiya van den Broek